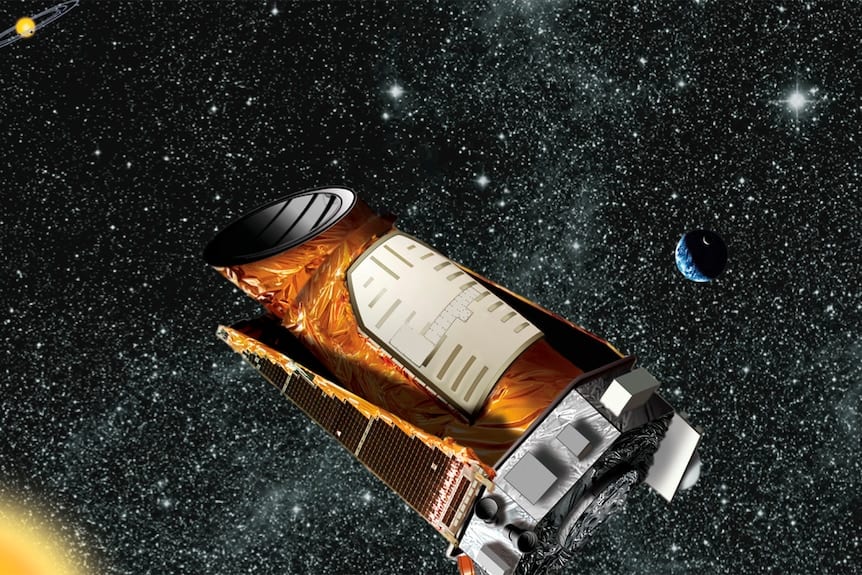

A few notable milestones include the discovery of the first transiting planet, HD 209456b ( Charbonneau et al., 2000 Henry et al., 2000) the discovery of the first exoplanet via transits, OGLE-TR-56b (whose photometric signal was first identified by Udalski et al., 2002, and whose planetary nature was confirmed via radial velocities by Konacki et al., 2003) the discovery of the first exoplanet via microlensing, OGLE 2003-BLG-235/MOA 2003-BLG-53Lb ( Bond et al., 2003) and the discovery of the first directly imaged planetary system around HR 8799 ( Marois et al., 2008). Since the discovery of 51 Peg b, many thousands of exoplanets have been discovered via many different techniques (see Figure 2.1). The discovery of 51 Peg b heralded a general principle that has since held in the exoplanet field-namely, that planetary systems are remarkably diverse, and to “expect the unexpected.” Indeed, this is still the prevailing wisdom, and thus the discovery of 51 Peg b led to the realization that at least some fraction of exoplanets undergo large-scale migration from their birthplaces. This is because the then-popular planet formation model predicted that such planets could not form in situ (e.g., Lin et al., 1996). The discovery of 51 Peg b, which has a minimum mass of roughly 0.5 times the mass of Jupiter (M J) but an orbital period of only about 4 days, surprised many.

Although it was not the first detected exoplanet (see Box 2.1), the discovery of a planetary companion to the near solar analogue 51 Pegasi by Mayor and Queloz in 1995 launched the field of exoplanets.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)